[upbeat drum based song]

LEO: Hello everyone and welcome to Changing the Frame. We are your hosts. My name is Leo Torre and I use he/they pronouns.

INDIGO: My name is Indigo Korres and I use she/her pronouns. We’re a podcast that discusses trends and non-binary experiences in the film industries. Every episode will count with the appearance of trans and or non-binary multimedia artists in the film industries to talk about their work. We are really excited to share these amazing talks and discussions with you all.

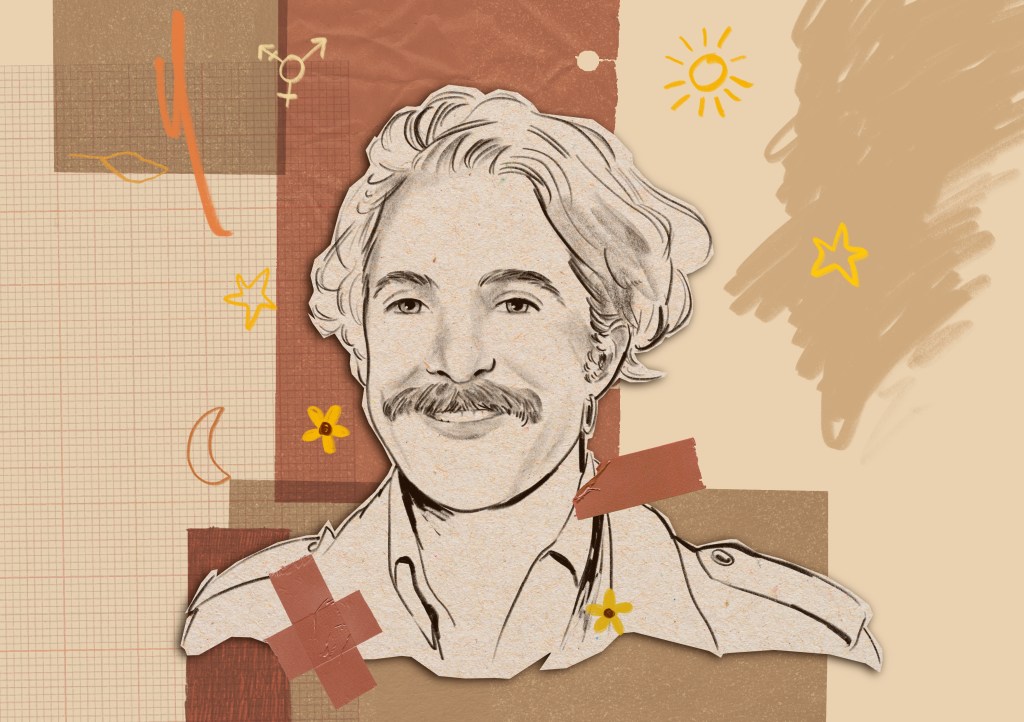

LEO: Today we have an incredible guest, Lyle Ravi Kash, who is a filmmaker and interdisciplinary practitioner who makes films with trans people about trans people. Kash’s debut film, Death and Bowling had an extensive festival run garnering awards from Outfest New Fest, LesGaiCine Madrid and Lovers Film Festival in Torino, Italy. Autostraddle called the film a fantasia on death and creation, stating that this is what we should be yearning for. Kash recently worked with the New York City Ballet and he is producing Angelo Madsen Minax’s A body to live in.

[upbeat drum based song]

INDIGO: This is changing the frame.

[upbeat drum based song fades]

INDIGO: Hello. Hello, Lyle, thank you so much for joining us today and discussing about your film, which is fantastic and almost literally made me cry. So I was just wondering if you could tell us a little bit about yourself and your background, hobbies, and other practice that you’re interested in.

LYLE: So I’m LyleKash. I use he/him, and I’m a queer and trans filmmaker. I live on the East Coast of the United States. I’m a dog dad. And I, yeah, I love watching films and making films and spending time outside.

LEO: That’s lovely. We were wondering what made you pursue filmmaking, because we read that you dreamed of pursuing a legal career beforehand and we’re wondering about the shift in careers and what kind of roadblocks you faced when you started filmmaking as well.

LYLE: Well, I come from a family of many lawyers and so I have a little bit of an argumentative streak, maybe a controlling streak. There’s these things are suited for directing as well, but yeah, I just like could not fucking imagine putting on a suit and going into a courtroom every day. Or, you know, I guess there are lots of different types of lawyers, but it seemed like a totally miserable, miserable life. My, my intentions as, you know, a possible attorney were to, to, you know, support social justice movements and act as like a wing for, for, for leftist movement building. However, I didn’t, I didn’t see a lot of work being done in the US from an attorney’s standpoint that didn’t result in like, total burnout or just like disconnection from reality. And, and I also wanted to live my life and I’m a creative person, so I, I, I see that was just not the right position for me. Though working with movement building organisations led me to filmmaking because, guess what, another thing, another type of movement building support is, is media literacy and media support. So it was an easy path and I think a lot of leftist movement building efforts are about, yeah, imagining a different world that doesn’t exist yet. And that’s, there’s a very similar relationship to storytelling and, and creating a film. So they feel like, yeah, linked together.

INDIGO: For sure. And how did you come up with the idea for this film when talking about filmmaking and what inspired Death and Bowling?

LYLE: You know, some kind of crazy storm of things, inspired Death and Bowling. I’m not a bowler. I don’t care for bowling. It’s embarrassing and I’m terrible at it. But, you know, I wanted to make a film about grief and I wanted to really stray away from, from fictional trans filmmaking that is, nearly so hyper real or has the goal of portraying such, you know, we’ve heard like accurate a presentation, blah, blah, blah, that I wanted to just be, I was not interested in making a documentary and I was not interested in making a documentary through fiction. So I wanted to deal with themes and images that were not entirely mine, though the story is extremely intimate and close to me. And, you know, the backdrop of bowling really came about because, it captured this theme of like, grief, American pastime. And I say grief because I think it’s like, it’s a, it’s a dying cultural space. It’s one that’s full of nostalgia in the states. It captures the generation that I portrayed on the Lavender League, but it’s also a site of like aesthetic nostalgia for millennials. And it also captures like, you know, that’s a space you can shoot in and, and rationalise why you have such a, like nostalgic images, because it’s also calling up like a generation of queer filmmaking. So that’s the backdrop. That’s how that came to be. And then the story I think is just like hodgepodge of personal experiences like, you know, me painting with a broad brush, like trying to come up with some like trans aesthetic themes and you know, poetics and blah blah blah.

LEO: That’s very good. Speaking about style especially as well, we were really into the film because it plays a lot into the abstraction and we thought that there was like many shots that were very dream-like, very like made up in the mind kind of situation, especially when like they’re both in the mountains and they have like the boxing gloves on and everything that felt like out of a dream instead of like real reality and how you speak about how you could have made a documentary, but you chose this instead. Is there any other forms of storytelling that you consider for this? Or like why? Why did you come about with these incredible shots and style for the film?

LYLE: Some of it is like first time filmmaker paying homage to all the films that I like, and then, you know, eventually you have to pick a genre, like maybe in the editing room, seriously. But, you know, there were times where this film was like a little bit more of a horror film where the emotional drama between the two main characters was a little bit more like, yeah, like holy, like moly, like, like, you know, not feeling so… I think it leaned more towards a romance, as the, as the project developed. But, you know, truly the feel and tone came about somewhat organically and by like beginner’s luck and through also like mistakes that I made and, just organic, yeah, attractions to certain types of cinema, especially like, you know, 1970s, 1980s European art house cinema. But, you know that scene that you’re talking about with the boxing gloves, some of that also, it feels like a dream cause it’s like, that’s like a hot fantasy to me. So I incorporated that and let it be the case that it either happened or it didn’t, but sort of who cares.

INDIGO: You mentioned a bit about the wanting to talk about death and grief is something that we see a lot in the trans community. And Death and Bowling mostly focuses around the death of a beloved character and what it means for everyone around her, so… however, this portrayal of grief is very positive. How did you develop that idea and put it into the film? To talk about it in a positive way as well? Because we see so many films around trans people that are just really, really bad when it relates to death. So, yeah.

LYLE: Yeah. And even if we’ve experienced a ton of that in our own lives, it’s like I, for one, Do not want to enter a cinema and like feel sad with a bunch of cis people about trans people dying. I’d rather like shave my eyebrows, you know? And so, however, you know, like what? What? You know, we, a lot of films, not just trans films, are also about grief and death and the best films that are about grief and death do it in the form of a comedy or they do it in the form of a horror film. You don’t make a tragedy about grief and death because it’s just a single note and like super flat. And I think that when we’re talking about like authentic representation and, and visibility, sometimes like that gets confused with like, we need to portray what actually happens in our lives, which like the honest piece is that that involves a lot of grief and death. That’s like part of the human experience. And I think, this, this possibility that trans artists can make something that’s actionally… Actually fictional or that we can begin to actually make art that’s about transness, allows us to take different forms to approach these themes. So I wanted to sort of like play the flute slightly differently but sing the same song. And so that’s, I think what Death and Bowling is also, you know, we, I really wanted to explore this idea that, and it’s a controversial one, that, that death, that suicide is a type of self-determination. It’s a choice that a person makes and I think that there are better choices. I wish that everybody had mental healthcare and family support and you know, that the state would had gave a shit about trans people at all. However, we deal with this topic as though it is like anathema to a self-determination politic. And so when X is addressing the fact that his friend or his mother figure, or however you wanna understands Susan and X’s relationship, he says like he basically, he feels that he can’t intervene because he’s trans and he’s made his own decisions about his body. And so I wanted to take a sort of like trans politic and present death in this way that, you know, just ask that question.

INDIGO: That’s so interesting.

LEO: Yeah. In, in talking about like X’s experiences of like what happened and like the death around him and everything, we realised that the colour palette in the film has a big role in how X explores all of these feelings. Cause the film begins with X wearing like darker colours and the leather jacket and everything. And by the end of it, he’s still wearing the leather jacket, but he’s wearing the lilac pastel and lilac yellow, yellow t-shirt underneath. And we’re like discussing this in the sense of like, he comes into his own by incorporating his mother figure as well. Is there any like specific decisions that you made with the colours in the filmmaking?

LYLE: Well, I definitely wanted lilac or purple to be a motif, kind of in the way that I was speaking about the bowling alley. Purple has had such an important history to, to queer and trans lives over a long period, and I wanted to tie some kind of, yeah, colour palette to the two generations that were portrayed in the film. Also he goes from wearing this leather jacket, which is sort of like a shell, like a protective armour. And it does, it’s not that he loses it, but I think like he allows himself like a little bit of colour to seep into his life and, and that purple throughout the film is, is just a callback to Susan. Like the purple screen comes up whenever she’s present, whether she’s dead or alive, and, you know, she’s the captain of this, this bowling league. This Lavander League, bowling league. And so he finally dawns the shirt because I think he, he experiences a sense of community by like letting go essentially.

INDIGO: Honestly, the colour palette was incredible.

LEO: Yeah.

LYLE: Thank you.

LEO: It was very good.

LYLE: Awesome.

INDIGO: When talking about Death and Bowling, do you feel like it’s helped you explore your identity deeper in any way whilst in the process of making the film?

LYLE: You know, that’s such a hard one because it’s also like a film takes, it’s, I’ve been working on it for like four or five years now and it’s finally spreading its wings and getting out in the world. So it’s like, I’m sure since it was such an important part of those five years, and you know, I’m 31 and not 26, so let’s all keep our fingers crossed that I like developed and matured in some way, like life of experience overall. But, you know, so much of how a filmmaker has changed by a film happens, you know, not just in the life of the film that’s on screen, but especially with such a community driven project like this, I can say for sure that, you know, I didn’t know any of the people I was going to work with prior to the film, and there are so many artists in my life now and, you know, actors who I now have like long-term friendships with. So yeah, my life was, was hugely changed and, and the way that I think about myself has shifted, you know, as I’m exploring this and talking out loud, I think, yeah, through those relationships also by bringing on a very intergenerational cast and crew. Yeah, there’s something really healing about doing that and being able to like, spend time with Tracy Kowalski, who is a different generation than me. And, and to imagine myself as a like gay, trans adult at his age is really nice because there are not so many people in my life who are of that generation. So I’m sure that in a long term way that will have like, hugely healing sweet effects on my little heart, you know.

LEO: For sure. For sure. And see how you speak about like having an intergenerational cast and like there was such a wide range of faces and people and Indigo and I were watching the film together and we were like, I can’t believe we’re like actually looking at this. Like we could see ourselves represented all through the film in like different ways and see people that we know kind of like it felt like it felt like coming home and the sense of community is really strong from that. Could you talk a little bit about how you casted an entirely almost trans cast?

LYLE: Well, oh my God. I love your question because, okay, here’s the sort of boring procedural part, which is like, I made some posts on social media and I was like, help, we’re doing this. Everybody contact me, you know, and a lot of people did and, and you know, we couldn’t even work with everybody who wanted to work on the project. So that’s sort of incredible and beautiful, although sad for the people who couldn’t work with it, that come on board for a future project. But then the other piece, you know, a lot of times cis people ask this question like, you know, why did the cast need to be all trans? Or like, how did you make this decision? Or da da da, which is a very different question. I mean, you’ve answered the question, which is that watching the film, you feel like you see people in your lives and it feels like coming home. Well, yeah. You know, like I wanted to spend the entire fall with a bunch of trans people, so I hired them. That’s, you know, like some of it is like, some of it’s like some kind of political position. Like yeah, it’s good. It’s gotta see trans people. It’s great. And the other piece is like, why would I wanna make a film differently?

LEO: Exactly. This is so good.

LYLE: And that piece that feels surreal, I think, to certain trans audiences who have never been in a room with mainly trans people or have never seen a reality in which like, there’s a range of gender performance and it’s difficult to predict how people identify, and that’s beautiful, and you’re just around trans people, and it’s magical. Great. If you’ve never seen that, that can feel like the most fictional sci-fi piece of the film, and for me, it’s the only part that’s documentarian.

LEO: Yes. Yes. Absolutely.

LYLE: Yeah.

LEO: Very much agreed with that because it was just like, even when you watch a film about trans people and everything, this just felt so natural to me because both Indigo and I move in like really queer circles already, so it was like, oh my God, nobody here is cis and, this is fantastic.

LYLE: Yeah.

LEO: Also like about how you mentioned wanting to like partake in leftist politics and everything, like I feel like this film really portrays that as well. And one of the scenes that really marked that for me was the funeral scene when they’re all talking. How did you write that?

LYLE: Oh man. Okay. Well here’s, here’s an embarrassing departure from, from our leftist politics discussion. So, so, okay. I mean, I just, I hesitate to say that this is a leftist film in any way, and the reason for that is it was community funded. Half the reason we couldn’t work with some of the people who wanted to work with us as we had no flipping money. So if you’re not paying someone a living wage, I’m sort of like, fine. It’s a community project. I get that there’s arguments to be made for like why it’s still beautiful that it happened, but I’m always like, oh God, we can’t call leftist or feminist or anything because I just couldn’t afford it. Which I know is a little bit of an oxymoron, but that aside, that funeral scene actually happened, you know, who knows how I wrote it? Maybe it is some sort of like impulse from like being in community and having, yeah, everyone wants to, it’s important to have everyone have a voice and blah, blah, blah. But we actually, we were gonna shoot that scene in a much more standard way, like in an Italian restaurant, and it was gonna be more like, You know, family dinner style and there’s lots of spaghetti and, and not that this is like a standard funeral and who knows how I wrote that either, but we, we lost the location because we didn’t know that it had a second donor and that person like had a total sort of transphobic freak out and we lost our contract and were like kicked out for the day. So we lost like two days of shooting and ended up doing it in the backyard of our Airbnb. So part of the feeling of it, which I, I think is so beautiful that on screen it reads to you as some like leftist gathering, but it was like, okay, everybody we’re doing this in one shot. Everybody got, you know, so, it’s a little like run and gone.

LEO: I feel like even though it’s like community funded and like, I, I feel like that that can still read very leftist cuz like this has been built by trans people for trans people, you know? And that really reads to me as like you care about the community, you’re doing things for the community. That’s just very leftist to me. So you’re all good in that sense?

LYLE: It is, it is. But I think we all have to sort of contend with this issue of like…

LEO: Yeah, for sure.

LYLE: …trans professionals being able to work in these types of sets that are funded. You know. It’s both, but thank you for saying that.

LEO: It really is both. Yeah.

INDIGO: In terms of trans filmmakers making their films and stuff, in what ways do you think it’s harder for minority identities to tell their own stories through filmmaking?

LYLE: Whew. Yeah, well, I’ll speak, you know, from the position of a trans filmmaker and I, you know, I think. Fundamentally, films require an audience. And they’re part of an industry even if you make them on a shoestring budget, if you want them to get seen in our current environment, right? You have to make them, there’s a market involved, blah, blah, blah. And in that market, I think legibility is like currency for trans films. So unless you have someone who is like pre pubescent in some trans way that’s unreadable, or they’re currently transitioning, or they chose not to transition so that a cis audience can see very clearly in their minds what their birth sex is. You’re not for an audience making a trans film unless you say over and over from an, you know, in the case of my film, at some point you needed to learn that the two protagonists were trans men or the film makes no sense. Like their relations make no sense. It’s impossible to read the film from a cis perspective. And there were things that came up around portraying trans characters who were not having a coming of age moment, but who were settled into their transness and living adult lives like after the coming of age moment, which is most of our lives, that, that, I had to really make decisions. I would’ve preferred to never use the word trans throughout the entire film and just have the film be presented in this way, but, I mean, you know how I did it? There were compromises that had to be made. But you know, there were even, like, I had experiences with other trans artists who were saying things like, you know, you should choose this shot cuz you could tell that he’s trans and I think the film won’t really read in this way, and I get exactly what they mean. And maybe that would’ve been a good decision and, here’s where the sticking point comes for, as you describe minority filmmakers, or I think just like, yeah, subcultural filmmakers. Or filmmakers making work about, yeah, non-normativity, whatever it is. Filmmakers who are making work that’s not about white people or rich people. And then if it’s not about those things, it’s not being told from this sort of like, ethnographical perspective. So when you’re making work about your own community, we have a way of seeing this film that’s very quick and easy and without those cultural reference points, even with as many signposts as I put in this film, which felt sometimes like I was like waving a fucking trans flag and be like, everybody, it’s a trans film. Okay. With that, you know, I screened the film in Italy last week to like total blank stares. Nobody knew. And at the end of the film, like there were questions like whose mom was who and like what? You know? And unless you spell out certain things to a non-trans audience, they continue in 2022 to not get it. And it’s not the audience’s fault, but where if you’re making it for a trans audience, it’s possible it’ll never be seen in the world ever. So I would say that’s the like, core problem. And if you delve into fiction, holy shit. I mean, it’s a, you’re, you’re, you’re already in a world that’s like difficult to understand and then you’re adding your own fictional rules from your fictional universe that’s already trans. I think it’s just we really need to be fighting for this fictional space because that’s where the sort of freedom of filmmaking is happening for, for a non-normative filmmaker who’s making work about their own community. And I think that gets missed sometimes.

LEO: What impact do you want your films to have then, like from, from now on? Not with just this one, but like from now on, what do you think are you trying to achieve? For both like the trans community and in general?

LYLE: I would love to be sharing like what I feel is beautiful about transness and how, you know, I see the world. I think that’s always part of a goal of a filmmaker. Whether it’s like completely egotistical or not. On some level, you’re sharing some kind of internal world or an imaginative world, and I, because I see so little of that, or I saw so little of that as a young person, I would really love to contribute to sort of like our generation’s trans aesthetics and, and fashion and like the imagery we use and to be part of like a, an artistic dialogue where like something from my film ends up in a poster and someone does a painting and there’s like conversation or you know, we’re also, I would love to be participating and referencing filmmakers or artists who came from the past, like I saw a film recently with a house on fire and I was like, okay, is this is David Wojnarowicz? And they had no idea what that was. So like how can we bring back the artist from previous generations in our own work to continue a sort of like ancestry of queer art that’s in conversational, so with dead people, that would be incredible. And also I would love to make a film that’s like, hot hot. Like that’s sexy with trans men in it. Do you know what I mean? They’re just, it doesn’t exist very much. It’s typically not hot. You know, you be the judge about Death and Bowling. But I would like to push my work in that direction in future projects.

INDIGO: That’s so good to hear. I would love to watch more of your films, so…

LYLE: Great. Okay. Okay. Help me find producers. Okay.

INDIGO: And talk about T4T relationships, I know you formed T4T Productions. And I was just wondering if you could tell us a little bit about it: how did you come up with the idea to form it. And also coming up with a different question, how accessible do you find funding opportunities for trans projects specifically?

LYLE: So I formed T4T Productions for, for… For listeners who don’t know, T4T, at least in my knowledge base, came from old Craigslist ads where you know, people would be like M4M and I was like, oh I’m a man, looking for a man to have sex with. But T4T obviously was trans for trans and blah blah. That has now disappeared. I’m not the only trans artist using T4T in my, you know, footnotes production, note my name of my company, blah, blah, blah. It’s widespread. I think like everyone on the planet now has some kind of T4T tattoo usually on their chest. Who knows? We all have one. Okay. T4T. Okay. So it seems like, it seems like a sort of obvious choice for, you know, a, a trans love story, and also trans love story that’s not really between two people, but but is a community and the film was trans and it was for trans people. Okay, we got that piece. In terms of trans funding, I think people wanna fund basically, like I said, like documentaries. And if it’s not a documentary, they want a fictional documentary that does the same work. And that’s because I think we’re in a stage where like trans media is supposed to still be like educating and… Yeah, I that, that feels a little sad to me because I think a lot of the work that gets funded ends up sort of playing like a workplace discrimination video where the plot of the film is one by one like, how do not offend a trans person or trans people accessing healthcare? And it ends up being this sort of like episodic, yeah, like training video that, that I don’t connect to myself. I think there’s a lot of work now not being made in that sorts type of format, but you’ll see that it’s almost entirely funded by communities on Kickstarter, private investors, because some lucky son of a gun found a rich person or you know, in a third case scenario, it’s in genre. So I think there is money for genre filmmaking like horror or blah blah, blah. If you’re not working in those capacities, I have literally no idea how to fund my second project. So, big, big question mark, you know?

INDIGO: Yeah. Cause most people that we’ve been talking to, they’re all like independent filmmakers. Yeah. So I wanted to ask that question because you are also in the US which is a different country. Like we’ve been talking mostly with people from the UK and it seems like it’s the same sort of process in the US.

LEO: The same struggle. Yeah.

LYLE: Yeah, it is. I would suspect, I mean, is there state funding for independent film? Like can you apply for state a little bit?

INDIGO: I mean we live in Scotland. The Creative Scotland does fund a lot of if independent projects, but it can be hard sometimes, depending on the project.

LEO: Yeah, there’s many hoops to go through and like applying and you know, that whole faf, but yeah.

LYLE: You know, I was just at like an industry event, blah, blah, blah, and there were a bunch of distributors speaking about, you know, how to, from a pre-production standpoint, you set up a queer film to get funding and then, and everything they were talking about, they were like having this nostalgia about filmmakers like Todd Haynes and Rayner Verner, Fassbender, and Greg Iraqi, blah, blah, blah. And we don’t see any of those equivalent filmmakers of our generation getting the funding because they would be, those filmmakers today would be completely unsellable. They’re sellable now because they’re names and there’s nostalgia for them. But that kind of work, that kind of like auteur, queer work is not getting funded. So I think actually we need to sort of like put all of our heads together and decide. , how are we going to seek like new models in this moment where that is absolutely not marketable and the only things that are getting funded are marketable, or they’re like sob stories, you know? So I think there has to be a third option.

LEO: Do you think you could speak about any new projects in the horizon for you?

LYLE: Yes. Yeah, I, in brief, you know, I’m making a film, I’m writing a, a screenplay right now that’s sort of like a, a trans take on the, on the, you know, the, the story of Pinocchio, not the Disney story of Pinocchio, but… but as we were finishing up Death and Bowling, a number of collaborators saw the opening scene and there’s a moment where X is in his casting tapes and he is being told to repeat over and over these lines. He said, I’m a real boy. And we were like, holy shit. It’s Pinocchio also. Like why has no one ever made a trans Pinocchio story? So it’ll be a totally, you know, nothing like Pinocchio, but wooden trans man will come alive for sure.

INDIGO: Talk about Pinocchio. There is this two trans artists in Scotland who did a play and is a take on trans Pinocchio as well. I think you should check it out. It’s by Ivor and Rosana.

LYLE: Oh, I would love to.

INDIGO: Ivor MacAskill and Rosana Cade. And we talked to them a few weeks ago and honestly, definitely check it out. I think they’re gonna tour it next month or in a couple months, but yeah.

LYLE: Oh my God. Well, please put us in touch also after.

INDIGO: I will. Don’t worry. But that’s so exciting.

LEO: The second you said Pinocchio, like my mouth dropped cuz we were like interviewing them like two weeks ago and it was so cute.

INDIGO: And honestly the line of I’m a real boy, like, yeah, it’s so trans, you know, like…

LYLE: it’s so trans.

INDIGO: Yeah. Sorry I went on a tangent, but yeah. Okay. So what advice would you. Share for transcend non-binary creators that are just getting started right now? That being in the US specifically or worldwide.

LYLE: I think my advice is to not worry so much about this funding piece as like a creative barrier, and I was given really good advice at some point, making Death and Bowling, which was like, even though you’re self producing, you have to take your producer hat off and not think about the budget or how you will solve these budget issues. Because otherwise, as you’re writing and you, you write the big car explosion scene or whatever you’re writing, you don’t need to like hamper the story by, in that moment as you’re writing, be like, we’re never going to be able to afford the, you know, the special effects for this explosion and the stunt guy and the car and blah, blah. You probably can’t. But write the story, write the story anyway, because I think so many filmmakers get really weighed down, and this is also part of why great fiction is not made because. Allowing yourself that imaginative space as though you have the biggest budget on the planet. Fix it later. When you’re having your producer hat on, you can bring someone in and be like, yeah, we can’t do the car scene, but what about the core story still exists? Like how, how can I create that at the budget level? That’s actually possible, but don’t do it in the beginning. Just write some incredible imaginative story.

INDIGO: I know you mentioned producing and writing and directing. So I just came up with a question in my head right now. So many trans filmmakers that I know are usually the heads of many departments in the process of production. How do you find that and how do you find tipping your toes into different departments during the production of your film?

LYLE: Well, I had never really made a film prior to Death and Bowling. I didn’t do the like shorts to feature route. I just made the film. And so my experience previously had been on, you know, much, much smaller sets and on much smaller sets everybody’s doing everything. So some of what happened with my film is like, I, I just filled in everywhere. Like where we were springing leaks from the ship. I like stuck my holes, like stuck my fingers in the holes. You know, it just was like instinct, like, oh, this email needs to get sent, da da da. And that ends up being producing unless you have like a robust production team that you’re paying full-time, which was not, you know, Ariel and I’s situation, we were both making other work and had jobs and blah, blah, blah, you end up just doing everything. And so on a larger production, that would be like the work of 15 people and on our size production, it wasn’t. So the answer is kind of like you, I’ve at least learned completely as I went along and in a cool way that’s translated to being able to like do paid work now on other sets, because I have the experience of just just having to throw myself into a feature. But I think also, you know, the art of producing is something that a lot of smaller trans productions in the US lack because no one can afford a professional producer, and it is an art. It’s not just something like administrative. And I think, you know, like when we were speaking about filmmakers from eras past or like, you know, Todd Haynes had this type of relationship with Christine Vachon. Like, where are the Christine Vachons of our generation? Because at this point it seems like they’re not being supported and don’t exist. And if they are creative, they’re directors, and if they’re not, it’s almost like a lot of, yeah, a lot of the sort of like idea of what producing is is like finding money in it and doing administrative work. But actually like those amazing auteur filmmakers existed because producers sought them out and were like, I am gonna make it possible for this filmmaker to make this film, and I just don’t encounter that anymore. So although it’s beautiful that we’re able to like fill in the gaps and do all this work on the production end, I think we really need to…. I really admire the support of like, organizations like Film Independent, that have like producer labs so that it’s a specific role. It actually shouldn’t be something that just gets like mushy, blended in with everybody else’s job.

LEO: We’re almost done, so we were just gonna ask you if you have any other media, so either like films, books, podcasts that you would like to recommend that have like either inspired you or you’re really enjoying right now.

LYLE: I mean, I loved Detransition Baby this year, I read that and felt it was truly exceptional. . Right now I’m producing a film for my friend and collaborator, Angelo Madsen Minax, and, and I think all of his filmmaking work is really incredible and sort of, you know, a lot of his work bridges the gap between narrative and documentary and so does this really interesting thing that we’ve been speaking about that I think is really important for trans cinema. His work also like totally kind of avoids like a, a huge focus on trans identity, but it’s all very trans to me. Ariel Mahler is at AFI right now and is making incredible films that none of you can see, but I’m sure that when they graduate they’ll make incredible films that you can all see. So keep an eye on their work. Oh shoot. I should have prepared for, for this one, but yeah. Everybody’s out there, use Google.

INDIGO: You can send us some recommendations later as well and we can share them on our social media. Where can people find you and your work?

LYLE: So, you know, Death and Bowling got distribution from from Wolfe Releasing this year. So at some point before the end of the year they will release the film. And so, you know, checking out Wolfe’s library of LGBT films is a good way to find Death and Bowling at some point, cause it’ll be there and you can watch it. And aside from that, you know, I have a website that I update every, like four months, but the, the piece of like work coming out as a filmmaker is slow enough that it’s pretty much up to date. So, so yeah, this film A Body To Live In that I’m producing, I’m sure I’ll share some information about how to see that. Also would, you know, my trans Pinocchio film, there will eventually be information. And I’m on Instagram, so, so @queerelle, which is like the Fassbinder film Querelle, but with an extra E, so it’s Q U E E R E L L E, and yeah, usually put stuff on there too.

INDIGO: Amazing. Thank you so much. Honestly, it’s been a pleasure to talk to you today.

LYLE: Aw, yeah. A huge pleasure for me as well. Thank you.

LEO: Thank you so much for letting us watch the film as well. It was a very enjoyable time and I. I, I think I speak for both Indigo and I saying that we’re definitely gonna watch it again soon. Cause I, I really enjoyed it and I think you’re doing fantastic work. So keep going.

LYLE: Thank you. That means a lot.

[upbeat drum based song]

INDIGO: This conversation has been incredible. We just want to thank LYLE so much for joining us today. It’s been a pleasure.

LEO: Make sure to follow Lyle on social media to get updates on Death and Bowling screenings and other work that he’s working on.

INDIGO: Thank you so much for listening to this amazing episode, and stay tuned for our following episode next month.

[upbeat drum based song fades]

Leave a comment